“Human sacrifice, judges and lawyers ‘friends’ on Facebook… mass hysteria!”

The greatest source of terror that lawyers face online is not from spyware, malware, phishers, or scammers. It’s from well-meaning regulators trying to apply legal ethics rules to the online world.

When legal ethics commissions wade off into a new area of technology, they can make truly scary rulings.

Judges are not and cannot be your “friend”

Last week, the Legal Profession Blog reprinted a decision from Florida’s legal ethics body that concluded lawyers and judges could not be “friends.” Not actually friends, of course — that’s permitted. What’s prohibited is being the sort of in-air-quotes “friend” listed with an online social media site.

The ruling is pretty stark, saying that judges cannot permit lawyers to add them as “friends” on social-networking sites. The commission’s concern was the impression that the online site might convey to the public that the “friend” has special influence over the judge. (( There is of course no surer way to build credibility as an advocate than letting a judge see all the high-school-yearbook pictures that your other friends post on Facebook. ))

The logic of this decision applies to Facebook friends, Twitter followers, and even Facebook fan pages

The “friending” concept the committee attacks would include most connection-based sites such as Facebook:

Whether a judge may add lawyers who may appear before the judge as “friends” on a social networking site, and permit such lawyers to add the judge as their “friend.”

ANSWER: No.

But the reasoning goes much further. The opinion explains that it applies even to a campaign committee that might set up a “fan page” on which people can list themselves as a supporter:

Whether a committee of responsible persons, which is conducting an election campaign on behalf of a judge’s candidacy, may establish a social networking page which has an option for persons, including lawyers who may appear before the judge, to list themselves as “fans” or supporters of the judge’s candidacy, so long as the judge or committee does not control who is permitted to list himself or herself as a supporter.

ANSWER: Yes.

That last phrase is the rub. The major social networking sites do let account owners “control who is permitted” to be a fan. (( I’m at a loss to see how this would be different than a campaign hosting a list of its supporters on its own website. But perhaps the Florida commission sees some ethical distinction I do not. ))

Twitter is obviously affected. Although you can “follow” someone on Twitter without them taking any action to accept you, Twitter lets account owners go back and “block” specific followers. (( I’ve never quite figured out why Twitter gives people this power to block “followers” on a public account — followers can do nothing more than read your public posts, which they could get on your public Twitter profile page even after you block them — but the power exists, and people use it. ))

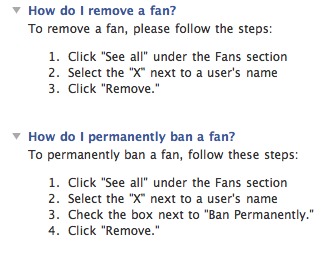

And the same is true of Facebook’s fan pages — which, presumably, the committee saw as different and through its “Yes” answer was trying to exempt from this rule. That’s because Facebook also lets owners of fan pages choose to block specific users:

Whoops! By trying to explain and narrow its ruling, the Florida commission seems to have just made the problem worse. Now it’s not just “friends” who are prohibited, but also “fans.”

What we need is common sense.

The commission’s attempt to draw a technological line between “friends” and “fans” didn’t work because the regulators had an incomplete view of how those websites work.

No doubt, some will say the regulators just need to find a more refined and even more technical distinction to use next time. But that’s a losing strategy. The technology is going to keep moving faster than our bar committees can keep up.

The right approach? Here’s what South Carolina said recently when asked if magistrate judges could be online “friends” with law enforcement officers:

CONCLUSION A judge may be a member of Facebook and be friends with law enforcement officers and employees of the Magistrate as long as they do not discuss anything related to the judge’s position as magistrate.

OPINION A judge shall respect and comply with the law and shall act at all times in a manner that promotes public confidence in the integrity and impartiality of the judiciary. . . . However, . . . complete separation of a judge from extra-judicial activities is neither possible nor wise; a judge should not become isolated from the community in which the judge lives. Allowing a Magistrate to be a member of a social networking site allows the community to see how the judge communicates and gives the community a better understanding of the judge. Thus, a judge may be a member of a social networking site such as Facebook.

That makes a great deal of sense. Cordoning off the legal system from the public will do nothing to boost public confidence.

If the only lawyers and judges that the public ever sees are the ones on television, we’re all in trouble.

Is social networking really the biggest concern about the public’s perception of judges?

At the same time Florida regulators are condemning Facebook, its trial bench judges still scrape together campaign contributions from local lawyers, as they must to win an election.

Imagine this as telephone poll:

“Which is a greater threat to judicial independence: (1) campaign contributions from people who later appear before the judge or (2) judges listing their friends on social networking sites like Facebook?”

The most popular response might be “Sorry, I just can’t stop laughing long enough to answer the question.”

Some people complain that they want more certainty about how legal ethics regulators will treat new areas of technology. But be careful what you wish for. It can be very wise for regulators to move slowly and avoid announcing bright-line rules about technology that’s so rapidly evolving.

Related story: While finishing up this post, I happened to hear this news story by Ben Phillpot on KUT that used this Florida ruling as a jumping off point to explore some related questions, like who can “friend” a lobbyist without triggering disclosure requirements.

3 responses so far ↓

1 Kendall Gray // Dec 17, 2009 at 7:27 am

So . . . it’s well accepted for a prominent lawyer to serve on a campaign committee and give or be responsible for tens of thousands of dollars in the campaign war chest . . . but . . . if you are Facebook Friends, then western civilization is placed at risk?

I wonder when we’ll see Facebook and social networking records folded into a Caperton recusal motion. {{shaking head in disbelief}}

2 Christina Sutt // Feb 14, 2010 at 12:55 pm

To answer the question in your footnote about why twitter lets you block followers… it’s because of spammers who follow people. There are two reasons to block them

1) It falsely inflates your “following” numbers, and some people like to track how many real people are interested in them. (Useful for people who use social networking for business purposes, like authors and agents.)

2) Some fans of people follow that person’s followers, because they think they have common interests, and the person being followed doesn’t want to be seen as endorsing a spammer or whatnot, so they block them.

3 Cross-post: Social media rules applying to lawyers and judges « Law of the Click // Feb 17, 2010 at 1:08 pm

[…] Cross-post: Social media rules applying to lawyers and judges Jump to Comments I wrote a post over on SCOTXblog titled “Judges friending lawyers on Facebook and social media: Florida’s clumsy overreaction.” […]